This is, quite frankly, bizarre. Mark Hughes, hardbitten product of the

Goulbourne Estate in Wrexham – a town whose present Labour MP swept into

office by a margin of more than 9,000 votes – is giving an interview over

tea and cocktail sausages at Manchester’s Winston Conservative Club. He is

here to deliver a £100,000 grant to help revitalise the local amateur

football teams. For in the game’s top-heavy pyramid such sides are an

endangered species, although not half as much as a Tory in Wythenshawe.

A sense prevails that for the firebrand Hughes, a fiercely loyal working-class

son of North Wales, this quaint setting is not a natural milieu. But one

habitat where he does appear increasingly settled is

Stoke

City, whose triumphs this season over Chelsea, Arsenal and

Manchester United have suggested a team dramatically rejuvenated under his

aegis.

Their most recent statement of intent, a free-wheeling 4-1 win at Aston Villa,

has even kindled talk of a first top-half finish in the Premier League.

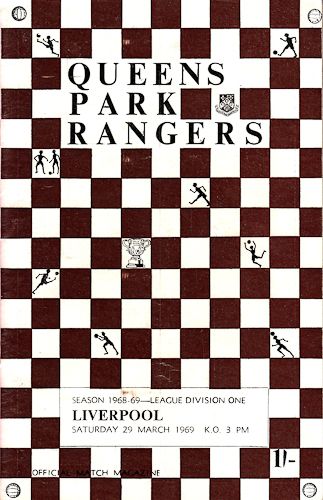

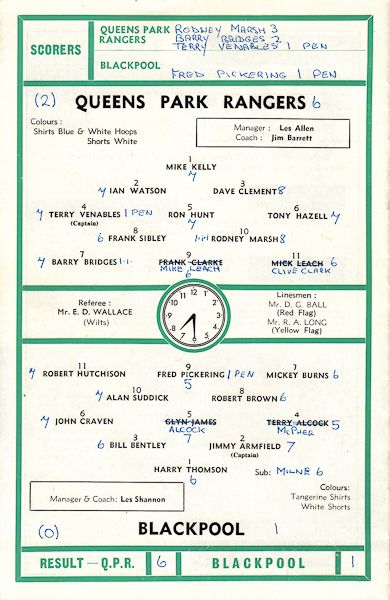

Somehow, despite the seething rancour and recrimination that disfigured his

stay at Queens Park Rangers, Hughes is legitimate top-flight stock once

more.

From the aesthetic poverty of Tony Pulis’s tenure – five straight seasons in

the Premier League, but an average of less than a goal per game – Hughes is

on course, provided his players successfully navigate the first of their

seven final games against

Hull

City on Saturday, to steer Stoke to the highest position, greatest

points total and most home wins in their six years at this level. Dare one

say it, but he has also, to judge by the thriving strike partnership between

Peter Crouch and Peter Odemwingie, made them a touch easier on the eye, too.

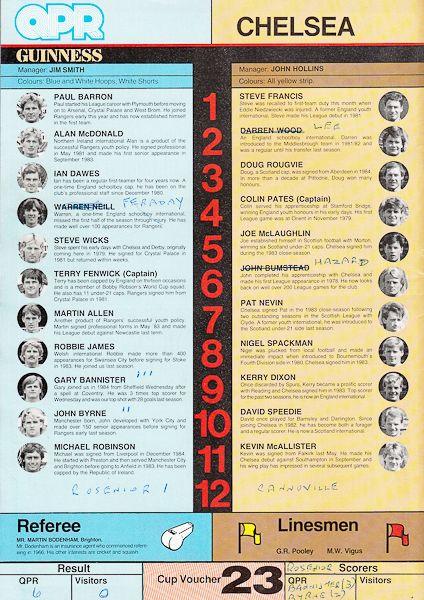

He is not about to deny, however, his part in the unravelling at QPR, whose

dressing-room culture was described by Ryan Nelsen as “the worst I have ever

seen”, or the blemish it left upon his reputation.

“When you have a situation like that, it’s something that stays with you for a

long time,” he says, reflecting upon his eventual sacking in November 2012.

“Three weeks ago it was my 300th game as a Premier League manager, but for a

long time yet at Stoke I will continue to be judged on the basis of 12 games

at the start of last season for QPR. Twelve games out of 300 – it’s a little

bit hard to take, because I feel I do understand what it takes to win at

this level. Unfortunately, for whatever reasons, we couldn’t get the right

dynamic at QPR. A lot of people put a great deal of effort and finance into

it, but it didn’t work. It was very difficult, but thankfully the owners at

Stoke looked beyond this, to what I had done at my previous clubs. They

didn’t see only those 12 games.”

Hughes has every reason to feel more content in the Potteries, given that

Stoke chairman Peter Coates, who appointed him last summer, lives locally

and has been a fan of the club from the cradle. Quite a contrast, then, to

QPR owner Tony Fernandes, who divided his attentions at QPR with his

business interests in Kuala Lumpur. “I have been taken aback by the warmth

of feeling at Stoke,” Hughes admits. “Subconsciously, you sense perhaps that

some people are expecting you to fail. I have never had that this season.

Stoke are a stable club who understand that there are peaks and troughs in

football, that you can lose games even if you do everything correctly.”

While Hughes’s accomplishments at Blackburn, whom he led to three successive

top-10 finishes, would withstand the sternest scrutiny, there is a suspicion

that he is still downplaying the extent of the QPR aberration. He can point

to the foolishness of Fernandes in lavishing an absurd salary upon Jose

Bosingwa, but the bald truth is that this most fastidious of managers – one

who takes pride in his nuanced knowledge of nutrition and sport science –

left QPR a basket-case of a club. Take an excerpt from the memoir by his

successor, Harry Redknapp, in which the attitude of first-team players is

portrayed as “arrogant and contemptuous” and where a “culture of decay” is

said to have taken root.

He sighs at the reminder, acknowledging: “Maybe I spread myself too thinly.”

Asked for extra detail, he explains: “An awful lot of things weren’t in

place at QPR. The training ground wasn’t ready and we were trying to address

that – we needed to create the right environment. But if you become too

wrapped up in all of that you can lose a grip on your players and what they

are doing on the pitch. I suppose I was being dragged into areas where I

needn’t have bothered.”

Plainly, Hughes is embarrassed by this chapter of his work. By turns wary,

brittle and circumspect when his QPR failures are raised, it appears he

would far rather dwell upon his recent rehabilitation. On the surface, his

methods at Stoke have evolved little: he has retained fellow Welshman Mark

Bowen as his ever-present deputy, and sources close to him confirm that the

50-year-old has lost none of his passion for vast screeds of ProZone data.

But results, as underlined by a sequence of only one defeat in eight, have

been emphatically revived.

Hughes risked derision when he declared that he would bring a more dynamic,

progressive brand of football to the Britannia Stadium, but he has since

found himself vindicated. “To begin with we were probably overdoing the

passing game, but Odemwingie has given us a little more of a cutting edge,”

he says. “We used to find it difficult to dominate games, but now we carry a

proper threat. We can be more direct, more quickly, but still have the

capacity to retain possession. The balance is where it needs to be.”

He defends his forensic approach, and his indulgence in such coach-speak as

“key performance indicators”, arguing that the “only reason I go into that

is because I believe it can make a difference in the Premier League. Here it

is about fine margins. You need to understand that or you’re not doing the

best by your team”.

Attempts to elicit what key texts might feature in his private library, or

whether he searches beyond sport for his inspiration, prove fruitless but

Hughes does offer his own intriguing slant on leadership. “I probably have

hundreds of books that I never read, but I just pick key sections from them

to use in the role I have. I wouldn’t say I am one for Churchillian

speeches, but they can be interesting to study.”

Hughes is uneasy about any intimation of criticism of his predecessor Pulis,

but he realises that any depiction of Stoke as one-dimensional, long-ball

brutes has been rendered redundant under his tutelage. “I was always

impressed by the technical ability of these players – that’s why I felt that

we could be a little different, that they could achieve more. We haven’t

spent much money, though. Of the bottom 10 clubs this season, eight have

smashed their transfer records, but we haven’t been anywhere near ours. We

have paid only £5 million on two players [Odemwingie and Marko Arnautovic].

We have changed, and yet we have kept the qualities of the best Stoke teams,

being difficult to beat and to break down. We have just added more strings

to our bow.”

For all his scrupulousness as a manager, not to mention his gifts as a player

for Manchester United, Barcelona and Bayern Munich, Hughes does continue to

make some peculiar decisions. It is odd in the eyes of many that a man of

considerable erudition would, for example, keep Kia Joorabchian as his

representative, aware of the agent’s controversial past and accusations that

he was influencing player contracts at QPR. “Kia’s just a friend and an

adviser,” he says, bristling slightly. “He hasn’t been involved

at Stoke, he’s just a guy whose company I like.”

Hughes can be acutely conscious of his public image. So as for whether he has

restored his good name in the wake of the QPR debacle, he resists sounding

too triumphalist. “I was quite prepared to allow others to take a view on

it,” he concludes. “I kept my own counsel and waited for the opportunity to

change people’s minds about my abilities. At Stoke, I’m allowed to work how

I want. All I hope is that people will now see I’m not too bad at what I do.”